Are European Countries Prepared for Attacks by Russian Drones Using Starlink?

The year 2025 has brought new lessons and new threats. Russian forces have begun the systematic and large-scale use of Starlink on their drones. Are other countries prepared for this type of threat?

Events in the second half of 2025 have shown that European countries are not ready for unmanned aerial drone attacks on their own territory. Ukraine possesses means to detect and destroy such drones and is constantly improving their effectiveness. European countries, however, significantly lag behind in this area and are forced to rely on more expensive and less effective solutions.

Ukraine has now faced new challenges — the mass and systematic use of Starlink satellite terminals on Russian drones is forcing a reconsideration of many issues. In particular, the tasks of detecting and neutralizing enemy drones equipped with such connectivity. Let us attempt to analyze how relevant this problem is for European countries, especially those that share borders with the so-called Russian Federation.

Anyone within European countries, regardless of their residency status in a particular state, can purchase a Starlink Mini terminal with an appropriate service plan. There are no additional identity or address verification procedures required for this. In most cases, it is sufficient to have a payment card from any bank, including a bank from another country. In other words, purchasing Starlink is actually easier than buying a SIM card with a phone number from any mobile operator in Europe. This is demonstrated, among other things, by cases of European Starlink terminals being procured for the Russian army.

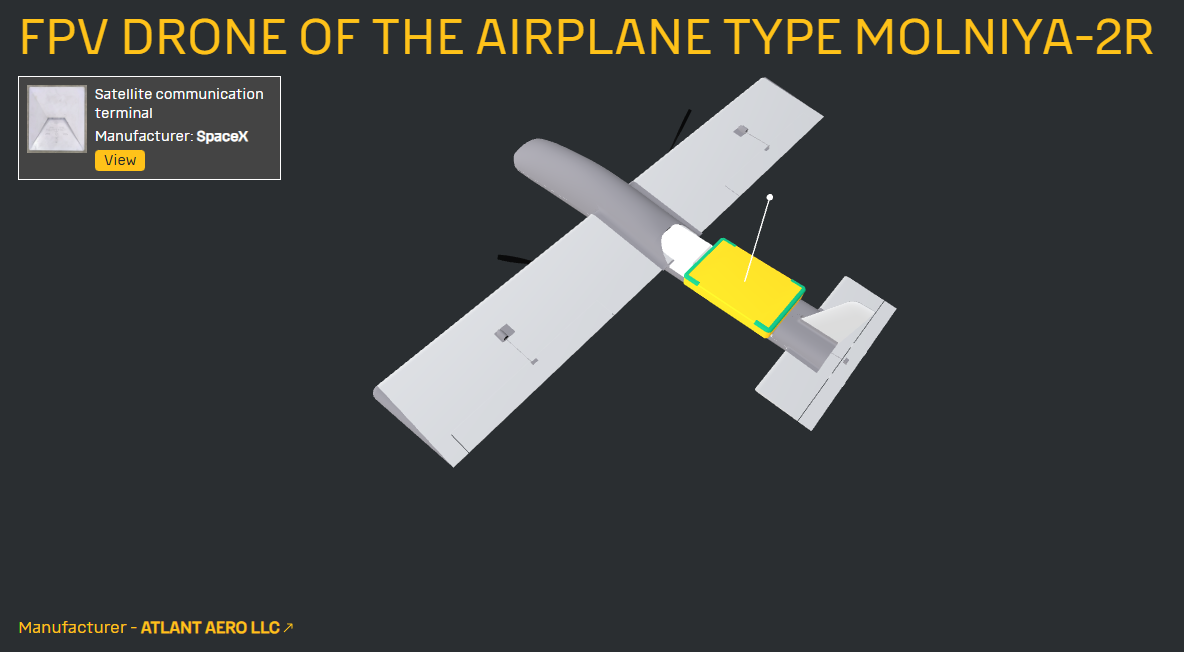

A Starlink terminal purchased in this way will function anywhere on the continent without restrictions, including operation on a moving vehicle. This is, of course, very convenient for many users. But are there any obstacles preventing a terrorist — including one hired by the special services of the aggressor state — from installing such a terminal on a drone carrying explosives directly within European territory? For example, on a “Molniya-2” or a “Lancet”? There is already substantial evidence of the manufacture and use of such drones by Russian forces in Ukraine. Assembling such a drone from components that are imported in one way or another does not appear to be a significant challenge.

Drones controlled via a satellite communication channel are extremely difficult to detect and almost impossible to suppress. The strike accuracy of such attack drones is extremely high — Ukraine is already suffering from this. So, is there any protection in Europe against such use of Starlink or OneWeb terminals? Are there control or regulatory mechanisms that take this risk into account and allow it to be reduced? Let us try to examine the answers to these questions.

Formally — and this is likely what politicians or civil servants in these countries would claim — certain control instruments do exist. In practice, however, these mechanisms and tools are effectively not adapted to scenarios involving the use of satellite internet on unmanned platforms. That is, there are currently neither barriers nor effective control mechanisms in place at all.

First, Starlink is a civilian communications system. It is not integrated into European airspace control systems, does not fall under classical real-time radio equipment licensing mechanisms, and has no mandatory linkage to a specific place of use or to any form of national registration. For the network operator, a terminal is merely a subscriber with coordinates, not an element of a potential weapon. Accordingly, no state perceives it as a threat until an incident occurs. Until the threat materializes…

Second, the radio monitoring and electronic warfare capabilities possessed by EU countries have historically been oriented toward other scenarios: protection of military bases, critical infrastructure facilities, and countering classical UAVs with line-of-sight radio links or GNSS navigation. A LEO satellite link with adaptive modulation, narrow beams, and high power represents a fundamentally different class of target. Suppressing or intercepting it requires an entirely different electronic warfare architecture, which European countries simply do not have deployed.

Third, there is an almost complete absence of a legal and regulatory framework that would account for the combination of a “civilian satellite terminal + unmanned platform.” A drone with explosives in Europe is still perceived as an exotic terrorist scenario rather than as a systemic military threat. As a result, there are no requirements imposed on drone manufacturers, no restrictions on integrating satellite terminals, and no mandatory mechanisms for remote shutdown or enforced geofencing at the state level.

Moreover, if such a drone were to use a cellular mobile network (5G, LTE, 3G), existing regulations would leave at least some possibility of tracking such a subscriber using the technical capabilities of national network operators. In the case of mobile satellite communications, such regulations and instruments simply do not yet exist.

A separate issue is detection. Over the years of war, Ukraine has built a multi-layered system: acoustics, optics, short-range radar, radio spectrum analysis, and data correlation. In most European countries, such systems either do not exist at all or exist only as pilot projects. At the same time, a drone equipped with Starlink does not require active local radio communication with a ground operator and therefore “emits” significantly less than classical FPV or commercial UAVs. Recent events demonstrate that detection capabilities for small drones are lacking almost universally over critical infrastructure sites across Europe. Such systems are quite expensive and require appropriate personnel expertise and integration solutions.

In practice, we are facing a situation in which a technology created for civilian internet access has significantly outpaced the ability of states to respond to its military conversion.

Ukraine is already living in this reality and is forced to adapt at an extreme pace. Europe, meanwhile, remains in a state of imagined security — the belief that drone warfare using satellite communications is “someone else’s problem” and does not affect its own citizens.

The key question here is not even Starlink itself. The question is whether European countries are ready to acknowledge that mass-market civilian technologies are no longer neutral. They can be integrated into weapons faster than laws, doctrines, and countermeasure systems can be developed.

And if the real answer to the questions posed at the beginning of this article is “no,” then the next logical question becomes even harsher: not “whether” a scenario involving drone attacks with satellite communications in Europe is possible, but “when exactly” it will cease to be theoretical and become practical. Especially against the backdrop of increasingly aggressive statements by Kremlin leadership toward Europe.

We already know that Russian strike drones equipped with Starlink are actively being used in Ukraine today. We also know that in addition to Starlink and OneWeb, several more global satellite communications operators are expected to become operational in 2026–2027 — Amazon LEO, Telesat Lightspeed, and others. Accordingly, the issue of mitigating the threats posed by the use of such communications systems on drones will only intensify.

It will be very interesting to see which countries prepare appropriate solutions first — Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, or Poland… Or will it be Germany, France, or others? In any case, the answer to all these questions will most likely become clear in 2026. Or perhaps it will not?